Posts in Category: Pet Health & Wellness

Meet Your Microbes

A few months ago, I had the opportunity to represent our clinic at a conference entitled Combating Antimicrobial Resistance with Stewardship, hosted by the Chicago Department of Public Health. It was wonderful to see professionals in all different sorts of medical fields come together to discuss topics that affect us all in how we manage our ever-developing love-hate relationship with these bugs that live all around and inside of us.

The average person has 38 trillion bacterial cells inside of them. These microbes are just as much of us and our pets as our very own cells. Bacteria are vital to our daily lives and the lives of our pets. Our understanding of our relationship with these little guys is constantly evolving. That’s why I feel it’s important to review some of the terminology related to the medications and practices used to manage bacteria.

Microbiome

This is a catchall word that refers to all the single-cell organisms that live in the body. The microbiome includes all bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa that can be found inside and on the body of any animal. There are good bugs and bad bugs. They can affect everything from the smell of our breath to rashes on our skin.

People often think “microbiome” relates just to the digestive system, but it also includes any organ system where these little ones can live, such as the skin, reproductive systems, oral cavity, and respiratory systems. For the most part, these organisms live in harmony with the animal’s body. When there is an imbalance, however, or some of these critters take up space where they don’t belong, the result can mean illness for us and our pets.

Probiotics

A probiotic is a bacterium that has been found to improve gut health. (You may see probiotic products for people for other parts of the body, but in veterinary medicine probiotics almost exclusively relate to the GI system.)

For our dogs and cats especially, gut health is determined by stool quality. Diarrhea in a pet is often a sign that pathologic (bad) bacteria and other microorganisms have overpopulated. In these cases, introducing a good bacteria can help reestablish balanced populations of bacteria and improve stool quality.

Many veterinary studies in recent years have shown that giving a probiotic helps control diarrhea faster than giving an antibiotic. Plus, probiotics may make diarrhea less likely to return in the future.

Antibiotics

These don’t need a lot of explanation, but just so that we’re all on the same page, antibiotics are medications that kill bacteria by targeting cellular function that is specific to bacterial cells and not our cells.

There are different kinds of antibiotics, categorized by what kinds of bacteria they attack, how powerful they are, and how they work (e.g., by killing the bacteria or just keeping them from reproducing).

The discovery of antibiotics is arguably the most important discovery of modern medicine. But it is also important to note that the more we use these drugs the less effective they can get. It’s vital that veterinarians and other medical professionals be judicious with their use.

Antiseptics

These are compounds that try to kill any microbial life. They don’t have to be specific to one type of bacteria or virus. These are most often used topically on the skin or cleaning surfaces. I feel that we often skip over antiseptics and think only of antibiotics, but antiseptics can be a valuable tool in keeping our pets healthy and keeping the bad bacteria under control

Prebiotics

This term is a bit newer to many of us. For a long time, most medical professionals thought you could manage the microbiome either by trying to take away bad bugs (using antibiotics and such) or by adding probiotics. Recently, attention has turned to prebiotics, especially among dog food companies.

Prebiotics are typically non-soluble (meaning we don’t absorb them) foods that the “good” bugs in the microbiome like. It may seem a bit obvious, but it’s a lot easier to put food into dog and cat food than to put probiotics into a food. A probiotic has to be alive to perform its function, but food is food. Prebiotics give the good bacteria the fuel they need to thrive, which is easier to do than delivering living good bacteria.

So, there’s your refresher! I hope it was a lot less painless than all of the microbiology classes I had to take in veterinary school. I still shudder thinking about trying to remember which viruses have cellular membranes or whether or not certain protozoa are found in certain chambers of a cow’s stomach.

Now go have a banana-oat-kefir milk smoothie and give those little buggers a treat!

Alyssa Kritzman, DVM

Feature illustration from AdobeStock images

Cold Weather Cautions for Your Pets

With cooler temperatures approaching, it is important to take precautions to keep your pets safe and warm throughout the winter months.

Prolonged exposure to extreme cool temperatures can lead to frostbite, causing tissue damage to exposed areas, and hypothermia, a life-threatening drop in body temperature. Senior pets, along with very young pets or those with chronic illnesses, are more vulnerable. This becomes important for dogs and cats with arthritis, as cooler temperatures can lead to stiff joints and increased pain in the winter months.

At temperatures above 45°F most dogs are comfortable and safe outside for regular activities like walks and playtime. However, temperatures 45°F or below can cause discomfort in small, thin-coated, senior, immunocompromised, or ill dogs.

Frostbite and hypothermia become risks at temperatures below 32°F, especially in breeds not adapted to cold climates. At temperatures below 0°F, dogs should be allowed outside only for short bathroom breaks. Even hardy breeds can suffer frostbite and hypothermia quickly in these temperatures.

Cats are more vulnerable as temperatures drop below 32°F. Cats should remain indoors as much as possible, as even short exposure can cause frostbite or hypothermia. Frostbite risk areas include ears, tails, and paws. These areas are most susceptible to frostbite because they have less fur and are prone to freezing.

Symptoms of hypothermia include shivering, lifting paws off the ground, whining or attempting to return indoors, lethargy, stiff muscles, slow breathing, and pale or blue gums. This can be life-threatening!

Precautions for Your Dogs

Know your dog’s cold tolerance and limit time outside. Try to keep your dog indoors as much as possible while ensuring that they get enough exercise. Shorten walks in extremely cold weather and keep your dog active indoors by providing enrichment and indoor play.

Avoid shaving your dog’s coat during winter as their natural fur provides insulation. Regular brushing can also help their coat retain warmth. Dry your dog thoroughly after exposure to rain or snow to prevent them from getting cold.

Use warm, durable winter coats and jackets, especially for short-haired or small breed dogs. Booties and paw wax protects paws from ice, snow, and harmful chemicals like salt. Consider protective paw balm to help prevent cracking and irritation from cold surfaces and ice melt. Rock salt and other chemicals used to melt snow and ice can irritate your pet’s paw pads and, if licked off the paws, their mouth. Be sure to wipe all paws with a damp towel before your pet licks them. Dogs are at particular risk of salt poisoning during the winter due to the rock salt used, often from licking their paws after a walk. There are many pet-safe ice melt options available.

Antifreeze has a sweet taste that may attract animals. Choose a pet-safe antifreeze because even small amounts of antifreeze can be lethal. Clean any antifreeze spills immediately and keep it out of reach. Coolants and antifreeze made with propylene glycol are less toxic to pets.

What About Outdoor Cats?

Outdoor cats need extra care as they often roam unsupervised. If possible, bring cats indoors during extreme weather. Subzero temperatures, snowstorms, or icy conditions are too dangerous for outdoor cats, so they should be temporarily housed indoors. If housing indoors is not possible, then providing outdoor shelter is very important. Create a weatherproof, insulated shelter with an entrance just large enough for a cat. Line the shelter with straw, as straw repels moisture and provides better insulation than blankets. Cats often seek warmth under car hoods so be very cautious when starting your car in the morning.

In freezing weather, outdoor cats might struggle to find unfrozen water or sufficient prey, leading to dehydration and malnutrition. There are many ways we can help keep outdoor cats safe this winter. Outdoor cats require extra calories to maintain body heat, so proper nutrition is important. Using heated water bowls and replacing water frequently is important to prevent freezing water. Avoid metal bowls as tongues can stick to frozen surfaces.

By taking these precautions, you and your pet can stay warm and healthy this winter.

By Dr. Angélica Calderón

Precauciones Para Sus Mascotas en Climas Fríos

Con la llegada de las temperaturas frías, es importante tomar todas las precauciones adecuadas para mantener a sus mascotas seguras y abrigadas durante los meses de invierno.

La exposición prolongada a temperaturas extremadamente frías puede provocar congelación, e hipotermia, una caída de la temperatura corporal potencialmente mortal. Las mascotas mayores y las muy jóvenes o aquellas con enfermedades crónicas son más vulnerables. Esto es importante para los perros y gatos con artritis, ya que las temperaturas frías pueden provocar rigidez en las articulaciones y aumento del dolor en los huesos.

A temperaturas superiores a 45 °F, la mayoría de los perros se sienten cómodos y seguros afuera para actividades como paseos y juegos. Sin embargo, las temperaturas de 45 °F o menos pueden causar molestias en perros pequeños, de pelaje fino, mayores, inmunocomprometidos o enfermos. La congelación y la hipotermia se convierten en riesgos a temperaturas inferiores a 32 °F, especialmente en razas no adaptadas a climas fríos. Los gatos son más vulnerables cuando las temperaturas caen por debajo de los 32°F. A temperaturas inferiores a 0 °F, deje que los perros salgan solo para breves descansos para ir al baño. Incluso las razas vulnerables pueden sufrir congelación e hipotermia rápidamente con estas temperaturas. Los gatos deben permanecer en el interior el mayor tiempo posible, ya que incluso una exposición breve puede provocar congelación o hipotermia. Las áreas de riesgo de congelación incluyen orejas, colas y patas. Estas áreas son más susceptibles a la congelación porque tienen menos pelaje y son propensas a congelarse.

Los síntomas de hipotermia incluyen escalofríos, levantar las patas del suelo, gemir o intentar regresar al interior, letargo, rigidez muscular, respiración lenta y encías pálidas o azules. ¡Estos pueden poner en peligro la vida!

Precauciones Para los Perros

Conozca la tolerancia al frío de su perro y limite el tiempo que pasa afuera. Trate de mantener a su perro adentro el mayor tiempo posible, pero asegúrese de que aún haga suficiente ejercicio. Acorte las caminatas en climas extremadamente fríos y mantenga a su perro activo en el interior brindándole enriquecimiento y juego en el interior.

Evite cortar el pelo de su perro muy corto durante el invierno, ya que su pelaje natural le proporciona aislamiento. El cepillado regular también puede ayudar a que su pelaje retenga el calor. Seque bien a su perro después de exponerlo a la lluvia o la nieve para evitar que se enfríe.

Utilice abrigos y chaquetas de invierno cálidos y duraderos, especialmente para perros de pelo corto o de razas pequeñas. Los botines y la cera para patas protegen las patas del hielo, la nieve y productos químicos como la sal. Considere utilizar un bálsamo protector para las patas para ayudar a prevenir la irritación causadas por las superficies frías y el hielo derretido. La sal de roca y otros productos químicos utilizados para derretir la nieve y el hielo pueden irritar las almohadillas de las patas de su mascota. Asegúrese de limpiar todas las patas con una toalla húmeda antes de que su mascota las lama e irrite su boca. Los perros corren un riesgo particular de intoxicación por sal durante el invierno debido a la sal de roca utilizada, casi siempre por lamerse las patas después de un paseo. Hay muchas opciones disponibles para derretir hielo apto para mascotas.

El anticongelante tiene un sabor dulce que puede atraer a los animales. Elija un anticongelante apto para mascotas, ya que el envenenamiento por anticongelante puede ser letal incluso en pequeñas cantidades. Limpie cualquier derrame de anticongelante inmediatamente y manténgalo fuera de su alcance. Los refrigerantes y anticongelantes elaborados con propilenglicol son menos tóxicos para las mascotas.

Y Los Gatos de Afuera?

Los gatos que viven afuera necesitan cuidados especiales, ya que andan sin supervisión. Si es posible, lleve a los gatos al interior durante condiciones climáticas extremas. Las temperaturas bajo cero, las tormentas de nieve o las condiciones heladas son demasiado peligrosas para los gatos que viven afuera y deben de mantenerlos temporalmente adentro. Si no es posible, es muy importante proporcionar refugio afuera. Cree un refugio aislado y resistente a la intemperie con una entrada lo suficientemente grande para un gato. Cubra el refugio con paja, ya que la paja repele la humedad y proporciona un mejor aislamiento que las cobijas. Los gatos suelen buscar calor debajo del capó de los coches, así que hay que tener mucho cuidado.

En climas helados, los gatos de afuera pueden tener dificultades para encontrar agua no congelada o presas suficientes, lo que provoca deshidratación y desnutrición. Hay muchas maneras en que podemos ayudar a mantener seguros a los gatos de afuera.

Los gatos de afuera necesitan calorías adicionales para mantener el calor corporal, por lo que una nutrición adecuada es importante. Es importante utilizar calentadores de agua y reemplazar el agua con frecuencia para evitar que se congele. Evite los tazones de metal ya que la lengua puede pegarse a las superficies congeladas.

Si toma estas precauciones, usted y su mascota podrán mantenerse abrigados y saludables este invierno.

By Dr. Angélica Calderón

How to Protect Your Pets from the Heat This Summer

Summer is a fantastic time to enjoy the outdoors with your pets, but the heat can pose serious risks to their health. High temperatures can lead to dehydration, heat stroke, and even burns from hot surfaces. Here are some essential tips to help you keep your furry friends safe and comfortable during the scorching summer months.

1. Hydration Is Key

Ensure your pets always have access to fresh, cool water. Consider placing multiple water bowls around your home and yard and check them frequently to make sure they are full. Cats usually prefer running water, so consider purchasing a water fountain. For outdoor activities, bring a portable water bottle and bowl so your pet can drink on the go.

2. Avoid the Heat of the Day

Plan your walks and outdoor playtime for early morning or late evening when temperatures are cooler. The midday sun can be intense and dangerous, increasing the risk of heat stroke and burned paw pads from hot pavement.

3. Provide Shade and Ventilation

If your pet spends time outside, make sure they have access to shaded areas. Trees, tarps, or umbrellas can provide relief from direct sunlight. For pets kept indoors, ensure your home is well-ventilated and consider using fans or air conditioning to keep the environment cool.

4. Never Leave Pets in a Parked Car

Even with the windows cracked, temperatures inside a parked car can soar to dangerous levels within minutes. Leaving your pet in a hot car can lead to severe heat stroke or death. If you need to run errands, leave your pet at home in a cool, safe environment.

5. Watch for Signs of Heat Stroke

Heat stroke is a serious condition that requires immediate attention. Symptoms include excessive panting, drooling, lethargy, vomiting, diarrhea, and collapse. If you suspect your pet is suffering from heat stroke, move them to a cool area, offer small amounts of water, and seek immediate veterinary attention.

6. Grooming and Coat Care

Regular grooming can help keep your pet’s coat free of mats and tangles, which can trap heat. However, be cautious with shaving; a pet’s coat provides protection against sunburn and helps regulate their body temperature. Consult your vet or a professional groomer for advice on the best grooming practices for your pet’s breed.

7. Cool Treats and Activities

Help your pet beat the heat with frozen treats and toys. You can make simple ice treats by freezing their favorite snacks in water or broth. Kiddie pools and sprinklers can also provide a fun way for pets to cool off while playing outdoors.

Pro tip: As always, make sure to clean the ears with a veterinary-approved ear cleaner after any water interactions to help prevent ear infections.

8. Mind Hot Surfaces

Pavement, sand, and even artificial grass can become extremely hot and burn your pet’s paws. Before taking your pet for a walk, test the surface with your hand. If it’s too hot for you to touch, it’s too hot for your pet’s paws. Stick to grassy areas or wait until the ground cools down.

9. Regular Health Check-ups

Ensure your pet is up to date with their health check-ups and vaccinations. Some conditions can make pets more vulnerable to heat, and a healthy pet is better equipped to handle the stress of hot weather.

10. Tick and Flea Prevention

Summer is the peak season for ticks and fleas, which can pose serious health risks to your pets. Use veterinarian-recommended tick and flea preventatives regularly. Check your pet’s fur and skin after outdoor activities, especially in wooded or grassy areas. Remove any ticks promptly using tweezers and consult your vet if you notice any signs of flea infestations, such as excessive scratching, red bumps, or hair loss.

By taking these precautions, you can help your pets stay safe, healthy, and happy during the summer heat. Enjoy the sunny season with your furry friends, knowing you’ve done your part to protect them from the dangers of high temperatures.

Stay cool and have a wonderful summer!

— Dr. Ana Valbuena

Cómo Proteger a tus Mascotas del Calor este Verano

El verano es un momento fantástico para disfrutar del aire libre con tus mascotas, pero el calor puede representar serios riesgos para su salud. Las altas temperaturas pueden provocar deshidratación, golpes de calor e incluso quemaduras por superficies calientes. Aquí tienes algunos consejos esenciales para ayudar a mantener a tus amigos peludos seguros y cómodos durante los calurosos meses de verano.

1. La Hidratación es Clave

Asegúrate de que tus mascotas siempre tengan acceso a agua fresca y fría. Considera colocar varios tazones de agua alrededor de tu hogar y jardín y revisarlos con frecuencia para asegurarte de que estén llenos. Los gatos suelen preferir el agua corriente, así que considera comprar una fuente de agua. Para las actividades al aire libre, lleva una botella de agua portátil y un tazón para que tu mascota pueda beber en el camino.

2. Evita el Calor del Día

Planifica tus paseos y el tiempo de juego al aire libre para temprano en la mañana o tarde en la noche cuando las temperaturas son más frescas. El sol del mediodía puede ser intenso y peligroso, aumentando el riesgo de golpes de calor y quemaduras en las patas por el pavimento caliente.

3. Proporciona Sombra y Ventilación

Si tu mascota pasa tiempo afuera, asegúrate de que tenga acceso a áreas sombreadas. Los árboles, lonas o sombrillas pueden proporcionar alivio del sol directo. Para las mascotas que se quedan en el interior, asegúrate de que tu hogar esté bien ventilado y considera usar ventiladores o aire acondicionado para mantener el ambiente fresco.

4. Nunca Dejes a las Mascotas en un Auto Estacionado

Incluso con las ventanas entreabiertas, las temperaturas dentro de un coche estacionado pueden elevarse a niveles peligrosos en minutos. Dejar a tu mascota en un coche caliente puede llevar a un golpe de calor severo o la muerte. Si necesitas hacer mandados, deja a tu mascota en casa en un entorno fresco y seguro.

5. Observa los Signos de Golpe de Calor

El golpe de calor es una condición seria que requiere atención inmediata. Los síntomas incluyen jadeo excesivo, salivación, letargo, vómitos, diarrea y colapso. Si sospechas que tu mascota está sufriendo un golpe de calor, muévela a un área fresca, ofrécele pequeñas cantidades de agua y busca atención veterinaria inmediata.

6. Cuidado y Mantenimiento del Pelaje

El aseo regular puede ayudar a mantener el pelaje de tu mascota libre de nudos y enredos, que pueden atrapar el calor. Sin embargo, ten cuidado al rasurar; el pelaje de una mascota proporciona protección contra las quemaduras solares y ayuda a regular su temperatura corporal. Consulta a tu veterinario o a un peluquero profesional para obtener consejos sobre las mejores prácticas de aseo para la raza de tu mascota.

7. Golosinas y Actividades Refrescantes

Ayuda a tu mascota a combatir el calor con golosinas y juguetes congelados. Puedes hacer golosinas sencillas congelando sus snacks favoritos en agua o caldo. Las piscinas para niños y los aspersores también pueden proporcionar una forma divertida para que las mascotas se refresquen mientras juegan al aire libre. Consejo: Como siempre, asegúrate de limpiar las orejas con un limpiador de orejas aprobado por un veterinario después de cualquier interacción con el agua para ayudar a prevenir infecciones de oído.

8. Cuidado con las Superficies Calientes

El pavimento, la arena e incluso el césped artificial pueden volverse extremadamente calientes y quemar las patas de tu mascota. Antes de sacar a tu mascota a pasear, prueba la superficie con tu mano. Si está demasiado caliente para tocarla, está demasiado caliente para las patas de tu mascota. Quédate en áreas con césped o espera hasta que el suelo se enfríe.

9. Prevención de Garrapatas y Pulgas

El verano es la temporada alta para las garrapatas y las pulgas, que pueden representar serios riesgos para la salud de tus mascotas. Usa preventivos contra garrapatas y pulgas recomendados por el veterinario regularmente. Revisa el pelaje y la piel de tu mascota después de actividades al aire libre, especialmente en áreas boscosas o con hierba. Elimina cualquier garrapata rápidamente usando pinzas finas y consulta a tu veterinario si notas cualquier signo de infestación de pulgas, como rascado excesivo, bultos rojos o pérdida de pelo.

10. Revisiones de Salud Regulares

Asegúrate de que tu mascota esté al día con sus chequeos de salud y vacunas. Algunas condiciones pueden hacer que las mascotas sean más vulnerables al calor, y una mascota saludable está mejor equipada para manejar el estrés del clima caluroso.

Tomando estas precauciones, puedes ayudar a tus mascotas a mantenerse seguras, saludables y felices durante el calor del verano. Disfruta de la temporada soleada con tus amigos peludos, sabiendo que has hecho tu parte para protegerlos de los peligros de las altas temperaturas.

¡Mantente fresco y ten un maravilloso verano!

— Dr. Ana Valbuena

Why Should You Spay or Neuter Your Dog or Cat?

Ovariohysterectomy (Spay)

Did you know that 25% of female dogs that are not spayed develop mammary tumors? Mammary tumors are commonly diagnosed in older intact female dogs, and the incidence of the development of mammary tumors in dogs is even higher than in humans.

A spay surgery, also called an ovariohysterectomy, involves the removal of the ovaries and uterus in a female dog. Although it is an invasive surgery, it is one of the most common surgeries performed in a general practice veterinary clinic.

There are many benefits to spaying your pet, and the earlier your pet is spayed the better. Complications that may arise during a female dog’s life if she is not spayed include mammary tumors/cancer and pyometra (infection of the uterus).

Additionally, spaying a dog or cat helps reduce pet overpopulation.

Mammary Cancer Risks

As previously mentioned, during a spay the uterus and both ovaries are removed. Ovaries are the female gonads that are responsible for the production of eggs and the female sex hormones, estrogen and progesterone.

Spaying a female dog reduces her risk of developing mammary cancer. If spayed before her first heat cycle, there is almost no risk that she will develop mammary cancer. After she experiences one heat cycle, the risk goes up to 7%. And after more than one heat cycle, the risk goes up to 25%.

Most mammary tumors in dogs are diagnosed between the ages of 9 and 11 years old. Risk of this tumor type is not associated with a specific breed. Small breed dogs, however, appear to be more affected. This suggests a possible genetic component, although one has not yet been identified.

According to information from Cornell University’s Richard P. Riney Canine Health Center, 50% of mammary tumors are malignant. The only way to determine if a tumor is malignant is to remove it and send it to a histopathology laboratory for interpretation.

Mammary Cancer Signs and Diagnostics

Clinical signs of mammary tumors include swollen glands, a painful abdomen, discharge from glands, ulcers near the mammary chain, and lethargy. An easy test that can be performed at most primary care veterinary clinics is called a fine-needle aspirate. This is a non-invasive test that extracts cells from the growth so that a histopathology laboratory can determine if they are cancerous.

A biopsy is a test that is more invasive than a fine-needle aspirate but less invasive than surgical mass removal.

Surgical removal is recommended if mammary cancer is suspected. Diagnostic tests performed before surgery include blood work and chest radiographs to see if the cancer has spread. Treatment ultimately depends on the type of tumor and its behavior.

If you notice any of the clinical signs for mammary cancer in your female dog, please contact your veterinarian.

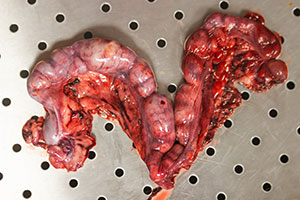

Pyometra in Dogs

A pyometra is a life-threatening bacterial infection of the uterus that is caused by hormonal changes in an intact female dog. A pyometra is most common in older intact females, but an unspayed dog of any age could get a pyometra. It can occur 1 to 2 months after a heat cycle.

There are two forms of pyometra, closed and open. An open pyometra—the most common form—is when the cervix is open and infection/discharge drains from the vulva. Clinical signs include malodorous discharge from the vulva, lack of appetite, lethargy, vomiting, and drinking an excessive amount of water. Sometimes there are no clinical signs in an open pyometra. Even so, dogs can decline rapidly if not diagnosed early.

Image by Kseniia from AdobeStock.

With a closed pyometra, the cervix is closed, and the discharge/infection remains inside the uterus. The uterus can rupture in a closed pyometra, and the pet can become septic. This is a medical emergency. Pyometra can be life threatening and the treatment is an emergency spay. Pyometra can be 100% prevented if a female dog is spayed early in life.

Pyometra in Cats

Cats also get pyometra. One major difference in cats, however, is that they rarely appear sick until the very late stages of pyometra. Their abdomen can appear larger and distended due to the size of the discharge-filled uterus. Cats are seasonally polyestrous, meaning that they go into more heat cycles than dogs do, which makes them especially susceptible to getting a pyometra.

As mentioned, an ovariohysterectomy (spay) is a routine procedure performed by many general practice veterinarians. If your female cat or dog is not spayed, please reach out to your local veterinarian to discuss spaying your pet.

Castration (Neuter)

A neuter, also called a castration, involves removing both testicles in a male dog. Testes produce sperm and the male sex hormone testosterone, which is essential for the function of the prostate.

Problems that can arise if a male dog is not neutered include benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), prostatitis (infection of the prostate), and testicular cancer. Various studies have shown that neutering a male dog can also help with mounting behavior, inappropriate elimination, and aggression.

Like a spay, a neuter is also a routine procedure and can be performed by most primary care veterinarians. Cats are often neutered under just sedation; the procedure can take less than 5 minutes in cats.

It is highly recommended to neuter your pet after 6 months of age. There is, however, controversy in regard to large breed dogs and bone growth/development. Neutering a large breed dog early has been shown to affect bone growth and lead to joint issues in the future. In a shelter setting, pets are usually neutered at an earlier age to make them more adoptable.

If your male dog/cat is not neutered, please reach out to your local veterinarian to discuss surgery.

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

Over the course of an intact male dog’s life, the prostate gland gradually enlarges due to the constant hormonal secretion. As an intact male dog ages, the prostate continues to enlarge and that can lead to discomfort/pain. This condition, called BPH, can ultimately interfere with defecation and urination.

Clinical signs of BPH include blood in the urine, difficulty urinating/defecating, and incontinence. An enlarged prostate can often be detected during a rectal exam. These signs however are very nonspecific and can resemble other medical conditions, such as a urinary tract infection, bladder stones, bladder crystals, or bladder tumor.

Neutering a male dog causes the prostate to shrink due to decreased hormonal secretion, which resolves BPH. If a dog has BPH, he will likely need anti-inflammatories and pain medications until surgical removal of the testicles. Ultimately, removing the testicles (neutering) is the treatment of choice.

Testicular Cancer

Testicular tumors are the most common genital tumors found in intact male dogs. Most testicular tumors are malignant, which means they have the potential to spread to other parts of the body.

Testicular tumors usually occur in older dogs, with an average age of 10 years old. The tumors can grow on one or both testicles. Clinical signs include asymmetric testicles, pain near groin, testicular swelling, and visibly larger testicle/testicles. Other signs include poor appetite, weight loss, and lethargy.

Treatment of choice is neutering the pet. Depending on the type of cancer, further treatment such as radiation or chemotherapy might be needed. Diagnostics, including blood work and chest radiographs to check for cancer spread, are performed before surgery.

Neutering your pet eliminates the risk of testicular cancer. If your male dog is intact and you would like to schedule a neuter surgery, please reach out to your veterinarian.

Cystine Crystals/Stones

The amino acid cystine can be excreted in the urine and can lead to the formation of bladder and kidney stones. Although cystine crystals and stones are rare, they are influenced by the presence of sex hormones. These types of crystals and stones are common in intact male dogs and require surgical removal.

Clinical signs may include straining to urinate, blood in the urine, and frequent urination episodes. Due to the anatomical difference in males and females, urinary obstruction is more common in males and it is a medical emergency.

Please reach out to your local veterinarian to further discuss spaying and neutering your pet, as there are many great benefits and various complications can be avoided if performed at an early age.

By Dr. Angélica Calderón

Images of Medical District staff and patients by Veronica

Por qué deberías esterilizar y castrar a tu perro/gato?

Ovariohisterectomía (esterilización)

Sabías que el 25% de las perras que no están esterilizadas desarrollan tumores mamarios? Los tumores mamarios se diagnostican comúnmente en perras mayores intactas y la incidencia del desarrollo de tumores mamarios en perros es incluso mayor que en humanos.

Una cirugía de esterilización, también llamada ovariohisterectomía, consiste en la extirpación de los ovarios y el útero de una perra. Aunque se trata de una cirugía invasiva, se realiza con mucha frecuencia y es una de las cirugías más comunes que se realizan en una clínica veterinaria de medicina general. Hay muchos grandes beneficios de esterilizar a su mascota y cuanto antes se esterilice a su mascota, mejor. Pueden surgir varias complicaciones a lo largo de la vida de una perra si no está esterilizada. Esto incluye tumores/cáncer mamario, piometra (infección del útero) y sobrepoblación de perros/gatos si se crían y producen descendencia, especialmente en la comunidad de animales callejeros.

Cáncer de mama

Como se mencionó anteriormente, durante una esterilización se extirpan el útero y ambos ovarios. Los ovarios son las gónadas femeninas que se encargan de la producción de óvulos y de las hormonas sexuales femeninas (estrógeno y progesterona). Esterilizar a una perra puede ayudar en gran medida a reducir la posibilidad de desarrollar cáncer de mama, independientemente de la edad. Sin embargo, hay varios factores a tener en cuenta. Si una perra es esterilizada antes de su primer ciclo de celo, la probabilidad de que desarrolle cáncer de mama es de casi el 0%. Después de experimentar un ciclo de celo, ese número sube al 7%. Si una perra experimenta más de un ciclo de celo, el número sube al 25%. La mayoría de los tumores mamarios se diagnostican entre los 9 y los 11 años de edad. No hay predilección por la raza, sin embargo, los perros de razas pequeñas parecen estar más afectados, lo que sugiere un posible componente genético. Sin embargo, aún no se ha identificado una mutación genética. Según el Centro de Salud Canina Richard P. Riney de Cornell, el 50% de los tumores mamarios son malignos y la única forma de determinar si un tumor es maligno es extirparlo y enviarlo para su interpretación histopatológica.

Los signos clínicos de los tumores mamarios incluyen glándulas inflamadas, abdomen doloroso, secreción de glándulas, úlceras cerca de la cadena mamaria y letargo. Una prueba fácil que se puede realizar en la mayoría de las clínicas veterinarias de atención primaria se llama aspirado con aguja fina. Se trata de una prueba no invasiva que se realiza habitualmente para evaluar el tipo de células presentes en el crecimiento. Estas muestras se envían para su interpretación histopatológica para evaluar si el crecimiento es canceroso. Otra prueba que se puede realizar es una biopsia, que es más invasiva que un aspirado con aguja fina, pero menos invasiva que la extirpación quirúrgica de masas. La extirpación quirúrgica es la recomendación de elección si se sospecha cáncer de mama. Se realizan varios diagnósticos antes de la cirugía; Estos incluyen análisis de sangre básicos, así como radiografías de tórax para evaluar la metástasis (diseminación). El tratamiento depende, en última instancia, del tipo de tumor y de su comportamiento. Si se observa alguno de los signos clínicos mencionados anteriormente en su perra intacta, comuníquese con su veterinario local para que se realicen los siguientes pasos apropiados.

Piometra

Una piometra es una infección bacteriana del útero potencialmente mortal causada por cambios hormonales en una perra intacta. Esto es más común en hembras mayores intactas debido a los diversos ciclos de celo de que han pasado, sin embargo, una perra intacta de cualquier edad es susceptible de contraer una piometra. Esto puede ocurrir de 1 a 2 meses después de un ciclo de celo y los signos clínicos incluyen secreción maloliente de la vulva, falta de apetito, letargo, vómitos y beber una cantidad excesiva de agua. Hay dos formas de piometra, cerrada y abierta. A veces, no hay signos clínicos en una piometra abierta, sin embargo, las perras pueden decaer rápidamente si no se diagnostican a tiempo. Una piometra abierta es cuando el cuello uterino está abierto y la infección/secreción drena fuera del cuerpo fuera de la vulva. Esta es la forma más común. Con una piometra cerrada, el cuello uterino se cierra y la secreción/infección permanece dentro del cuerpo en el útero. De esta forma, el útero puede romperse y la mascota puede volverse séptica. Esto es una emergencia médica. Una piometra puede poner en peligro la vida y el tratamiento para esto es una esterilización de emergencia. Esto se puede prevenir al 100% si una perra es esterilizada a una edad temprana.

Lo mismo se aplica a las gatas, sin embargo, una diferencia importante en las gatas es que rara vez parecen enfermas hasta las últimas etapas de la piometra. Su abdomen puede parecer más grande y distendido debido al tamaño del útero lleno de secreción. Las gatas son estacionalmente poliestroles, lo que significa que entran en más ciclos de celo que las perras, lo que los hace especialmente susceptibles a contraer una piometra.

Como se mencionó, una ovariohisterectomía (esterilización) es un procedimiento de rutina realizado por muchos veterinarios de práctica general. Si tu gata o perra no está esterilizada, comunícate con tu veterinario local para hablar sobre la esterilización de tu mascota.

Castración

Una castración consiste en extirpar ambos testículos en un perro macho. Los testículos producen espermatozoides y las hormonas sexuales masculinas (testosterona), que son esenciales para la función de la próstata. Pueden surgir varios problemas si un perro macho no está castrado. Esto incluye la hiperplasia prostática benigna (HPB), la prostatitis (infección de la próstata) y el cáncer testicular. Se han realizado varios estudios que muestran que la castración de un perro macho también puede ayudar con el comportamiento de montaje, la eliminación inapropiada y la agresión. Al igual que una esterilización, una castración también es un procedimiento de rutina y puede ser realizado por la mayoría de los veterinarios de atención primaria. Los gatos a menudo son castrados bajo sedación y el procedimiento real puede tomar tan solo menos de 5 minutos en gatos. Se recomienda encarecidamente castrar a su mascota después de los 6 meses de edad, sin embargo, existe controversia con respecto a los perros de razas grandes y el crecimiento/desarrollo óseo. Se ha demostrado que la castración temprana de un perro de raza grande afecta el crecimiento óseo y provoca problemas en las articulaciones en el futuro. En un refugio, las mascotas suelen ser castradas a una edad más temprana debido a fines de adopción.

HPB (Hiperplasia Prostática Benigna)

A lo largo de la vida de un perro macho intacto, la glándula prostática se agranda gradualmente debido a la constante secreción hormonal. A medida que un perro macho intacto envejece, la próstata continúa agrandándose y eso puede provocar molestias o dolor. Esto se denomina HPB (hiperplasia prostática benigna) y, en última instancia, puede interferir con la defecación y el orine a medida que la próstata continúa agrandándose.

Los signos clínicos de la HPB incluyen sangre en la orina, dificultad para orinar/defecar e incontinencia. Sin embargo, estos signos son muy inespecíficos y pueden parecerse a otras afecciones médicas como una infección del tracto urinario, cálculos en la vejiga, cristales en la vejiga o tumor en la vejiga. La castración de un perro macho hace que la próstata se encoja debido a la disminución de la secreción hormonal cuando se extirpan los testículos, lo que en última instancia previene la HPB. Si un perro tiene HPB, es probable que necesite antiinflamatorios y analgésicos. La extirpación total de los testículos (castración) es el tratamiento de elección.

Cáncer testicular

Los tumores testiculares son los tumores genitales más comunes que se encuentran en perros machos intactos. La mayoría de los tumores testiculares son malignos, lo que significa que tienen el potencial de propagarse a otras partes del cuerpo. Los tumores testiculares suelen aparecer en perros mayores con una edad media de 10 años. Pueden crecer en uno o ambos testículos y los signos clínicos incluyen testículos asimétricos, dolor cerca de la ingle, hinchazón testicular y un testículo o testículos visiblemente más grandes. Otros signos incluyen falta de apetito, pérdida de peso y letargo.

El tratamiento de elección es la castración de la mascota. Dependiendo del tipo de cáncer, es posible que se necesite un tratamiento adicional como radiación o quimioterapia. Se realizan varios diagnósticos antes de la cirugía, como radiografías de tórax para evaluar la metástasis (diseminación) y análisis de sangre. Castrar a tu mascota eliminará el riesgo de cáncer testicular. Si tu perro macho está intacto y deseas programar una cirugía de castración, comunícate con tu veterinario.

Cristales de cistina

El aminoácido cistina puede excretarse en la orina y provocar la formación de cálculos en la vejiga y los riñones. Aunque los cristales y cálculos de cistina son raros, están influenciados por la presencia de hormonas sexuales. Este tipo de cristales y piedras son comunes en los perros machos intactos y requieren cirugía.

Los signos clínicos pueden incluir esfuerzo para orinar, sangre en la orina y episodios frecuentes de micción. Debido a la diferencia anatómica en machos y hembras, la obstrucción urinaria es más común en los machos y se trata de una emergencia médica.

Comunícate con tu veterinario local para hablar más sobre la esterilización y castración de tu mascota, ya que hay muchos beneficios y se pueden evitar varias complicaciones si se realiza a una edad temprana.

By Dr. Angélica Calderón

Images of Medical District staff and patients by Veronica

Mystery Canine Respiratory Illness

Fear of the Unknown, or Fear of Saying ‘I Don’t Know’?

Originally, I was planning to write this blog about the current “mystery illness” that is popping up in random places around the United States. But when I sat down to research what I could, I kept getting stuck on the word “unknown.” It made me think about all that I haven’t figured out myself yet.

“I don’t know” is a phrase that you are likely to hear from me as your pet’s veterinarian. It is a phrase that I used to be terrified of saying when I first started practicing medicine over a decade ago.

I spent a lot of time (most of my 20s) and money (over six figures) learning everything about biology, chemistry, pharmacology, virology, physiology, anatomy (of multiple species, mind you!), really any animal-related “-ology” so I could avoid that very phrase.

Why I Say ‘I Don’t Know’

Now, with years of experience in the field, I frequently say “I don’t know” because I am so acutely aware that figuring out why an animal is sick (we call this a differential diagnosis) is often much harder than just making an animal feel better (we call this empiric therapy).

There are a few reasons why this is so:

- Answers often cost money. Even the best veterinarians can go only so far on a physical exam and asking good questions. Eventually we need test results, but this costs money—your money—and sometimes we don’t need an answer to find the treatment. We want to put your resources to the best use. If we use up the available budget to find answers, that may mean we have fewer resources to provide the care your pet needs.

- Answers often aren’t easy. One of the worst things that has ever happened to any medical professional is the show CSI. They always find the answer in a convenient hour (or 40 minutes if you’re paying for premium streaming). This is just not reality. Yes, sometimes tests to give you a precise answer, but a lot of times testing provides information and clues. Then I use my expensive degree to put all the pieces of the puzzle together.

- Answers often aren’t universal. This is what I mean when I say a pet “hasn’t read the textbook.” The same problem does not always manifest in the same way in every pet. (Not to put all the blame on cats, but it’s usually cats who haven’t read the textbook!) That can mean that even if we think we know what’s going on, we can get curveballs.

I know this may not instill a lot of confidence in what I and my colleagues do, but I say this because I want you to know that getting an answer isn’t my only goal. I want to help you and your pet in the best way possible. Often these goals are at odds with each other.

We Still Don’t Have an Answer

This brings me to the current “crisis” going on in veterinary medicine right now: the mystery respiratory illness that is affecting dogs. We still don’t have an answer as to what it is. It won’t be easy or cheap to figure out, but there are people working on it. As soon as we have verified information, we will let you know.

For now, we’re left with the general guidance of trying to keep your dog away from crowded canine events as much as possible (I will be boarding my own dog over the Christmas because that’s our only option), keeping them away from unhealthy dogs, and keeping up with the recommended respiratory vaccines like distemper, bordetella, and parainfluenza, and, for some dogs, influenza.

It’s hard accepting “we don’t know,” but to tell you anything more than that would be foolish. In all my years of practice, I would much rather say “I don’t know” than “I was wrong.”

—Dr. Alyssa Kritzman

Diabetes in Cats: Prevention and Treatment

Diabetes mellitus is a condition in which the body cannot properly produce or respond to the hormone insulin. Insulin regulates the amount of glucose (sugar) in the bloodstream and delivers glucose to the tissues of the body to use as energy. Diabetes results in elevated levels of glucose in the blood. The most common form of diabetes in cats is type 2 diabetes. In type 2 diabetes, glucose levels are high because cells in the body do not respond appropriately to insulin.

Diabetes is the second most common endocrine disease in cats. (The body’s endocrine system consists of several glands—in the case of diabetes, that gland is the pancreas—that make hormones, which are chemical messengers to control organs throughout the body.)

Cats are typically diagnosed with diabetes between the ages of 10 and 13 years. More cats are acquiring diabetes as the number of overweight or obese cats grows. The average cat that weighs 13 pounds or more has about four times the risk of developing diabetes as a smaller cat. Signs of diabetes can include increased thirst, increased urination, weight loss, and increased appetite.

Diagnosis

When a cat is suspected of having diabetes, a veterinarian will perform blood and urine testing. Diabetes is indicated if blood testing shows an elevated glucose level (hyperglycemia) and urine testing shows evidence of glucose in the urine (glucosuria).

Because stress in cats can lead to both hyperglycemia and glucosuria, another confirmation test called fructosamine is usually done. Fructosamine concentration reflects the average glucose concentration for the past 1 to 2 weeks and is not impacted by stress. If this test comes back as elevated, the diagnosis of diabetes is confirmed.

Treatment

Insulin is the treatment of choice for cats with diabetes. This typically requires twice daily administration. In addition, dietary management can be an important component of managing diabetes in cats. A high-protein/low-carbohydrate diet is recommended. Weight loss is also an important component of diabetic management in overweight cats. Weight loss, if attempted, should ideally be gradual, one-half percent to 1% of total body weight lost per week.

The goals of treatment are to maintain a healthy blood glucose, stop or control unintended weight loss, stop or control increased thirst and urination, and avoid hypoglycemia (low blood glucose).

Unlike dogs, cats can reach diabetic remission; these cats have near-normal blood glucose levels without receiving insulin or other blood-sugar–lowering medication. However, cats in diabetic remission require close monitoring to ensure that they do not relapse. Remission is not achievable in every diabetic cat.

Monitoring

Blood glucose curves are used to monitor response to insulin dosing. If a blood glucose curve is performed at home, pet owners measure the first blood glucose reading before the insulin injection. Then, they test every 2 to 4 hours until the next dose of insulin, depending on the type of insulin used. Performing curves at home eliminates the stress of coming to the clinic, which can affect the accuracy of the testing. Owners may need to perform a blood glucose curve several times to find the right dose for their cat.

One method of measuring glucose is by using a glucose meter calibrated for feline blood, such as a AlphaTRAK3. Another way is by using a continuous glucose monitor, such as a FreeStyle Libre. These monitors can be picked up at a human pharmacy and installed by a veterinarian or veterinary technician. Other important monitoring tests include serial bloodwork and urine testing. Your veterinarian will help determine the frequency at which these tests should be performed.

Monitoring your cat’s level of thirst and urination, weight, and appetite are important throughout treatment. These measures can give clues as to how well the diabetes is being managed. Unfortunately, monitoring response to treatment in diabetic cats can be frequent and expensive.

Complications of Diabetes

One complication of diabetes is diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). This problem occurs when there is not enough insulin in the body to control the amount of glucose in the blood. DKA happens in uncontrolled diabetics. Without the proper amount of insulin in the body, glucose cannot be used as an energy source. Instead, the body breaks down fat, which produces ketone bodies. With high levels of ketones, the body becomes more acidic, which disrupts fluid and electrolyte balance. Left untreated, the resulting abnormal electrolyte balance may lead to abnormal heart rhythms and muscle function and death. Signs of DKA can include increased thirst or urination, lethargy, weakness, vomiting, increased respiratory rate, decreased appetite, and weight loss.

The other complication is hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar, which may arise when insulin therapy lowers the blood sugar significantly. Signs of hypoglycemia include weakness, lethargy, vomiting, lack of coordination, seizures, and coma. Hypoglycemia can be fatal if left untreated. A diabetic cat that shows any of these signs should be offered its regular food immediately. If the cat does not eat voluntarily, it should be given oral glucose in the form of honey, corn syrup, or dextrose gels and brought to a veterinarian immediately. However, if a cat is seizing or comatose, oral glucose methods should not be attempted.

If you’ve noticed changes to your cat’s eating and drinking habits as well as weight, please have them seen by a veterinarian for additional testing to be done as soon as possible.

By Jeanette Barragan, DVM

Heartworms/Parásitos del Corazón

En español

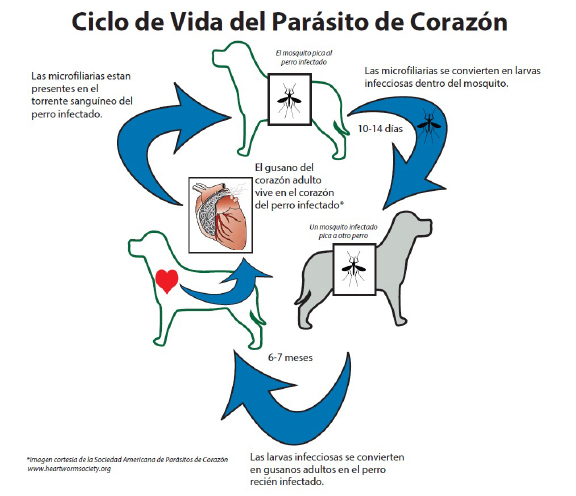

Con el verano acercándose, muchos de nosotros pensamos en el riesgo de las pulgas, garrapatas y parásitos intestinales pero no se olviden de los parásitos del corazón! El parásito del corazón es transmitido por los mosquitos y causa daño irreversible al corazón, las arterias, y los pulmones. No existe cura en los gatos y el tratamiento en los perros es costoso, doloroso, y toma un promedio de un año.

Muchos piensan que sus mascotas no están a riesgo de infección en Illinois como tenemos inviernos largos, pero solo se necesita una mordida de un mosquito que lleva el parásito para ser infectado. Aunque su mascota no salga de la casa, los mosquitos pueden entrar por las ventanas, garajes, puertas, etc.

Es importante realizar que la prevención no previene la exposición y aunque los medicamentos preventivos no matan al parásito adulto, se usan para prevenir la madurez de los gusanos. Si el medicamento preventivo se da sin prueba de diagnóstico y el perro está infectado, no solo se quedará infectado pero también puede causar reacción parecida a un shock. En casos inusuales, también puede resultar en fallecimiento de la mascota.

Los gusanos adultos parecen espagueti cocido y pueden llegar a 12 pulgadas. La carga parasitaria puede variar de 1 a 250 gusanos con un promedio en los perros de 15 gusanos! La severidad de los síntomas depende de la carga parasitaria, el nivel de actividad de la mascota, y cuánto tiempo ha estado infectado. Los síntomas más comunes son tos, dificultad para respirar, fatiga, falta de apetito, y pérdida de peso.

El mejor tratamiento es la prevención!

La buena noticia es que existen varios medicamentos preventivos para los perros y gatos! Se necesita una prueba negativa una vez al año (en los perros) para poder recetar el medicamento. Si su mascota no ha tomado la prevención del parásito del corazón de manera constante durante los últimos 12 meses, debería hacer una cita con su veterinario para hacer un análisis de sangre para comprobar un resultado negativo y poder recetar prevención. Hay varias formas de prevención y su veterinario le puede recomendar cual usar basada en su estilo de vida.

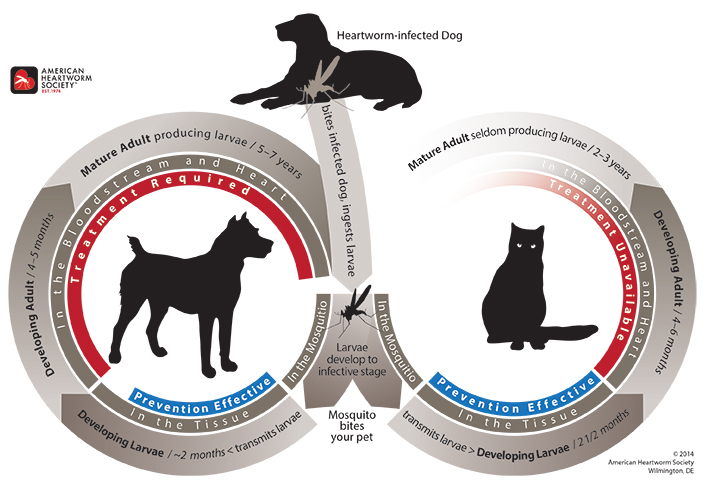

In English

With summer approaching, many of us think about the risk of fleas, ticks, and intestinal worms. But don’t forget about heartworms! Heartworms are transmitted by mosquitoes and cause irreversible damage to the heart, arteries, and lungs. There is no cure in cats, and treatment in dogs is expensive, painful, and takes an average of one year.

Many think that their pets are not at risk of infection in Illinois since we have long winters, but it only takes one bite from a mosquito that carries the parasite to be infected. Even if your pet does not leave the house, mosquitoes can enter through windows, garages, doors, etc.

It is important to realize that prevention does not prevent exposure. Although preventative medications do not kill the adult parasite, they are used to prevent the worms from maturing. If the preventative medication is given without a diagnostic test when the dog is already infected, the dog will not only stay infected but the medication can also lead to a shock-like reaction. In rare cases, it can also result in the death of the pet.

Adult worms look like cooked spaghetti and can grow to 12 inches. The parasite load can range from 1 to 250 worms, with an average of 15 worms in dogs! The severity of the symptoms depends on the parasitic load, the pet’s activity level, and how long they have been infected. The most common symptoms of a heartworm infection are cough, shortness of breath, fatigue, lack of appetite, and weight loss.

The best treatment is prevention!

The good news is that there are several preventative medications for dogs and cats! A negative test is needed once a year (in dogs) before the drug can be prescribed. If your pet has not been on heartworm prevention consistently for the past 12 months, you should make an appointment with your veterinarian for a blood test to confirm a negative result so prevention can be prescribed. There are various forms of prevention, and your vet can recommend which one to use based on your lifestyle.

– Dr. Ana Valbuena

The Itchy Pet

Para leer el blog en español, haga clic aquí

With Chicago’s changing weather, who knows what season we’re currently in right now? And with the season change comes … seasonal allergies, or just allergies in general.

That’s the tricky part that we veterinarians face. We have to investigate and determine what type of allergies your pet is experiencing, and if it is truly allergies versus something else.

As many of you may know, just like people get allergies, so do pets. The signs, however, can be a little different. Many times your pet will show signs of scratching, biting, chewing, and rubbing certain areas of their bodies. You can even see redness, inflammation, fur loss, and, in severe cases, open, infected wounds.

There are many components to allergies, and getting a detailed history from you during the initial vet visit is very important. So although it may seem like an interrogation in the exam room, this is when we are putting all of the puzzle pieces together in our head and thinking of the best diagnostic tests and treatment options for your pet. Each pet is different, and treatment varies on a case-by-case basis.

Flea Allergy

“My cat doesn’t go outside.” “My dog isn’t around other dogs.” “I’ve never seen any fleas on my pet.”

Just because you don’t see them, doesn’t mean they’re not there. Did you know that 1 female flea can lay between 20 and 50 eggs a day?

At times, the only evidence we have to suspect that there are fleas present is flea dirt, which is basically flea feces. Areas that can be affected by fleas include the tail base, neck region, and belly, although fleas can be found anywhere on the body.

A flea allergy is caused by the saliva of the flea itself. All it takes is a few bites to see clinical signs. Fleas can survive at a wide range of temperatures, so it is important to have your pet on flea and tick preventatives year-round to avoid flea allergy dermatitis. Read more about fleas.

Food Allergy

Pets can also have hypersensitivities to certain foods. Although potential allergens can include the food dye, carbohydrates, or preservatives, often it’s the protein source that is the culprit. A food allergy is diagnosed based on a detailed history and, most importantly, a strict food trial.

A food trial consists of feeding your pet a hydrolyzed diet or novel protein for a minimum of 8 weeks. This diet is very strict, and it is important that you only feed the novel protein or hydrolyzed diet. You must not feed any additional foods or treats. Keep in mind that many medications and monthly preventatives can be flavored so you must monitor closely what you are feeding and giving your pet. If after the trial period your pet is symptom free, a food challenge is performed. This consists of introducing the previously fed diet and watching for signs of itching or scratching. More details regarding a food trial can be discussed with your veterinarian. Read more about food allergies.

Seasonal vs Environmental Allergies

These can get tricky and hard to diagnose so, as previously mentioned, a thorough history becomes very important. We must investigate if there is any pattern to the clinical signs. Are the signs happening when it is warmer out vs colder? Do the signs show up after walks or after visiting certain areas, like a park or forest preserve? Every detail matters, so it is important to reach out to your veterinarian when your pet starts experiencing signs of excessive itching, scratching, licking, fur thinning, etc.

Treatment for Allergies

Treatment varies on a case-by-case basis. Ultimately, we want to control your pet’s clinical signs but also make your pet comfortable and clear of any secondary infections. Contact your local veterinarian when you start seeing any of the previously mentioned clinical signs.

There are several allergy medications to try. Each pet is different, and sometimes it can take some trial and error to find what works best for your pet, whether that is a single medication or a combination of medications. Allergy medications come in oral, injectable, and topical formats. Your veterinarian will determine which one suits you and your pet’s lifestyle.

Is It Even Allergies?

Although fur loss, fur thinning, over-grooming, and biting can be signs of allergies, these can also be signs of stress, especially in cats. Fur thinning and fur loss can even be signs of endocrine diseases, such as hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism.

If your pet is experiencing any of the clinical signs mentioned throughout this post, please reach out to your veterinarian so they can determine the best diagnostic test and treatment options for your pet. You and your veterinarian form a team that wants the best for your pet.

– Dr. Angelica Calderon

Comezón de la mascota

Con el clima cambiante de Chicago, quién sabe en qué temporada estamos ahora. Y con el cambio de clima llegan… las alergias. Esa es la parte difícil a la que nos enfrentamos los veterinarios. Tenemos que investigar y determinar qué tipo de alergias está teniendo su mascota y si realmente se trata de alergias o de otra cosa.

Como muchos de ustedes saben, al igual que nosotros podemos tener alergias, las mascotas también pueden hacerlo. Sin embargo, nuestros signos pueden ser un poco diferentes. Muchas veces su mascota puede mostrar signos de rascarse, morderse, y masticar ciertas áreas de su cuerpo. Incluso se puede ver enrojecimiento, inflamación, pérdida de pelo y, en casos graves, heridas abiertas infectadas.

Las alergias tienen muchos componentes y es muy importante obtener un historial detallado durante la visita inicial al veterinario. Entonces, aunque pueda parecer un interrogatorio en la sala de examen, al mismo tiempo estamos juntando todas las piezas del rompecabezas en nuestra cabeza y pensando en las mejores pruebas de diagnóstico y opciones de tratamiento para su mascota, ya que cada mascota es diferente y puede variar según el caso.

Alergia a las pulgas

“Mi gato no sale”, “Mi perro no está con otros perros”, “Nunca he visto pulgas en mi mascota”. Que no los veas no significa que no estén ahí. ¿Sabías que una pulga hembra puede poner aproximadamente de 20 a 50 huevos por día? A veces, la única evidencia que tenemos para sospechar que hay pulgas presentes es la suciedad de pulgas, que es básicamente heces de pulgas. Las áreas que pueden verse afectadas por las pulgas incluyen la base de la cola, la región del cuello y el vientre; aunque se pueden encontrar en cualquier parte del cuerpo. Una alergia a las pulgas es causada por la saliva de la pulga y nada más se necesita algunas picaduras para ver los signos clínicos. Las pulgas pueden sobrevivir en un amplio rango de temperaturas, por lo que es importante que su mascota tome medicamentos preventivos contra pulgas y garrapatas durante todo el año para evitar la dermatitis alérgica por pulgas. Leer más sobre pulgas.

Alergia a la comida

Las mascotas también pueden tener hipersensibilidad a ciertos alimentos. Aunque los alérgenos potenciales pueden incluir colorantes alimentarios, carbohidratos o conservantes; lo más común es la proteína que es la culpable. Una alergia alimentaria se diagnostica en base a un historial detallado y una prueba alimentaria estricta. Una prueba de alimentación consiste en alimentar a tu mascota con una dieta hidrolizada o proteína novedosa durante un mínimo de 8 semanas. Esta dieta es muy estricta y es importante que solo le des la dieta proteica o hidrolizada novedosa. No debe alimentar con alimentos adicionales. Tenga en cuenta que muchos medicamentos y preventivos mensuales pueden tener sabor, por lo que debe controlar de cerca lo que alimenta y le da a su mascota. Si tu mascota está asintomática, se realiza un reto alimentario que consiste en introducir la dieta alimentada previamente y vigilar si presenta signos de picor o rascado. Se pueden discutir más detalles sobre una prueba de alimentos con su veterinario. Leer más sobre alergias alimentarias.

Alergias Estacionales y Ambientales

Estos pueden volverse complicados y difíciles de diagnosticar, por lo que como se mencionó anteriormente, un historial completo y detallado se vuelve muy importante. Debemos investigar si existe algún patrón en los signos clínicos. ¿Están ocurriendo los signos cuando hace más calor que cuando hace más frío? ¿Aparecen los signos después de caminatas o después de visitar ciertas áreas como un parque o una reserva forestal? Cada detalle es importante por lo que es importante comunicarse con su veterinario cuando su mascota comience a enseñar signos de picazón excesiva, rascado, lamido, adelgazamiento del pelaje, etc.

Tratamiento para Alergias

El tratamiento varía según el caso. Queremos controlar los signos clínicos de sus mascotas, pero también hacer que su mascota se sienta cómoda y libre de infecciones secundarias. Esto significa comunicarse con su veterinario local cuando comience a ver cualquiera de los signos clínicos mencionados anteriormente. Hay varios medicamentos para la alergia para probar, sin embargo, cada mascota es diferente y, a veces, puede tomar un poco de prueba y error para finalmente encontrar lo que funciona mejor para su mascota. Qué puede significar un solo medicamento o una combinación de diferentes medicamentos. En cuanto a los medicamentos, hay varias opciones orales para probar, así como opciones inyectables y opciones tópicas. Su veterinario determinará cuál se adapta mejor a usted y al estilo de vida de su mascota.

¿Es incluso alergias?

Aunque la pérdida de pelaje, el adelgazamiento del pelaje, el aseo excesivo y las mordeduras pueden ser signos de alergias; estos también pueden ser signos de estrés, principalmente en gatos. El adelgazamiento y la pérdida de pelo pueden incluso ser signos de varias enfermedades endocrinas como el hipertiroidismo o el hipotiroidismo.

Si su mascota enseña alguno de los signos clínicos mencionados en esta publicación, comuníquese con su veterinario para que pueda determinar las mejores opciones de prueba de diagnóstico y tratamiento para su mascota. Somos un equipo y queremos lo mejor para tu mascota.

– Dr. Angelica Calderon

Osteoarthritis: It’s Not Just for Older Pets

Osteoarthritis in pets is often thought of as a geriatric pet disease that warrants treatment when our pets are obviously painful and experiencing lameness. However, osteoarthritis often starts younger than you might expect, and pain may be present even before lameness is apparent.

Let’s start with what osteoarthritis is: it’s the most common form of arthritis and it is characterized by painful inflammation and degeneration of one or more joints. Over time, it can lead to bone-on-bone contact.

Many factors contribute to the disease process, including overweight or obesity, abnormal joint development, past injury or orthopedic surgery, and how a pet is built.

In dogs, early signs of this disease can include:

- restlessness or irritability,

- frequent position changes during rest,

- not as fast getting up or sitting down,

- weight shifting while standing,

- less interest in activity or play, and

- hesitation before walking, sitting, or climbing stairs.

Eventually, a dog may begin to limp, to experience stiffness when walking, and to have difficulty going up or down stairs and jumping up or down.

In cats, osteoarthritis may look like a reduction in play, grooming, socializing, and appetite, with increases in hiding and sleeping and changes in urination/defecation habits. Cats can also have trouble jumping up/down, climbing up or down stairs, running, and chasing objects.

Because this disease is painful and progressive, early diagnosis and treatment are important for long-term pain management and slowing the progression of the disease. Treatment includes a combination of pain medication, weight loss or maintenance, dietary changes, environmental modification, and exercise.

If you feel your pet may be showing signs of osteoarthritis, our clinic can share additional resources on how to know if your pet has this disease and talk with you about treatment options.

– Dr. Jeanette Barragan

Photo by Madalyn Cox on Unsplash

COVID and Pets: An Update from the Frontline

After two long years of this pandemic, we still do not know much about pets and SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), but over the last few months I have learned a lot. I am writing this blog as I am isolated in my basement with COVID-19. I am thankful for the protection I have received from vaccines as I am only experiencing very mild signs.

I hope to tell you what I have learned working firsthand with the first Illinois COVID positive dog over the past few months. According to the USDA there have only been 39 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) positive dogs within the United States. The first dog in Illinois confirmed to be positive was a patient at Medical District Veterinary Clinic and was first tested in January 2022. He was positive on PCR, and viral sequencing information was obtained at the National Veterinary Services Laboratories in Ames, Iowa.

Since that time, I have had multiple other patients that are presumptive positives. A presumptive positive is when there is detection on a PCR test, but it is not confirmed positive with either virus sequencing or evidence of virus neutralizing antibodies. Obtaining sequencing data is challenging, most likely because the dogs have low viral load and very mild clinical signs.

Other resources

- USDA case definitions: SARS-CoV-2-case-definition.pdf (usda.gov)

- USDA Confirmed cases SAR CoV-2 in US: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/dashboards/tableau/sars-dashboard

- CDC Animal guidelines: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/animals.html#:~:text=The%20virus%20can%20spread%20from,pets%2C%20livestock%2C%20and%20wildlife.

Transmission

We believe that transmission to pets is from contact with a positive human within the household. Transmission from pets to humans is considered extremely low. Due to the risk of transmission to pets, the CDC recommend avoiding close contact with pets if you are ill. The occurrence of severe illness in pets is rare, but transmission is possible. Pets presumed positive should remain isolated from other pets until clinical signs have resolved.

Clinical Signs

It is important to remember this is a human pandemic. We know that by comparing the large number of human cases of COVID 19 and the very few cases documented in pets.

I truly believe that most pets do not acquire the virus. If they do, they are typically asymptomatic or have very mild symptoms. The clinical signs I observed in these presumptive positive cases were upper respiratory signs: nasal congestion, sneezing, reverse sneezing, and gag-like cough. These signs were odd and did not fit with classic tracheobronchitis (canine cough). When I examined these dogs, they did not cough when I touched their neck to palpate their trachea, which is the typical response during a physical exam when the patient has classic canine cough.

We have seen patients with clinical signs suspected to be secondary to SARS-CoV-2 in the past 2 to 4 weeks.

Treatment

Unfortunately, there is no approved or documented treatment for COVID in dogs or cats, but in most cases, they do not need treatment. For those pets with more severe clinical signs, I have found that corticosteroids seem to provide the most relief. The brachycephalic breeds seem to have more nasal congestion and difficulty breathing. In these pets, I have started anti-inflammatory doses of steroids and they seem to respond well.

In a few of these cases, chronic rhinitis (irritation/swelling of the mucous membrane in the nose) and sneezing has lasted for weeks to months. Home care for pets is similar to home care for most human COVID-19 cases. The virus needs to run its course. Be sure your pets continue to eat and drink. You can also put the pets in the bathroom with the shower running; the warm humid air can be soothing for the upper airway.

Testing

SARS-CoV-2 testing is not widely available for dogs or cats, but most large veterinary laboratories are offering PCR testing. Antibody testing is not widely available at present. If you feel you dog or cat has signs of SARS-CoV-2 after exposure to an infected person, I recommend contacting your veterinarian.

If you are a client at Medical District Veterinary Clinic, feel free to reach out to me and I may be able to assist in testing as I am collaborating with Dr. Ying Fang, a virologist, at the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine.

– Dr. Drew Sullivan